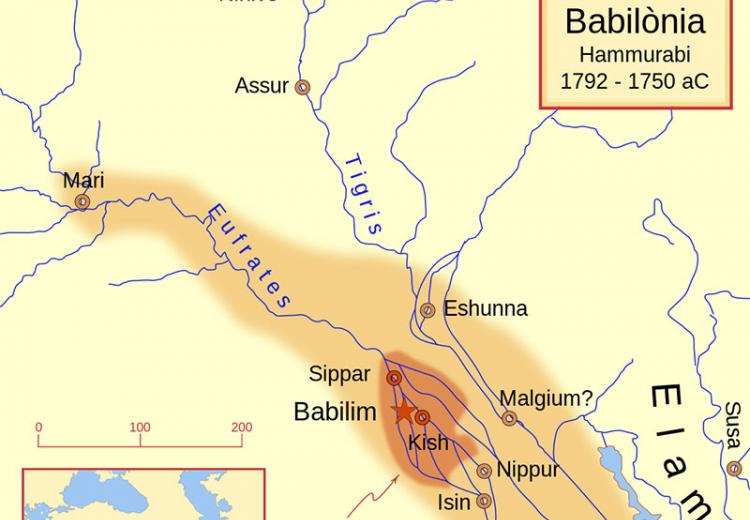

In approximately 1764 BCE, a coalition led by the city-states of Elam and Eshunna invaded Babylonian territory, hoping to capture Hammurabi’s powerful realm, but it failed, and Hammurabi turned his attention to the south. Soon Babylon had become a major center of power in the south and the target of rival kingdoms. This pact gave him the protection he needed to expand his kingdom, taking control of Isin, Uruk, and other key cities of southern Mesopotamia. Early in his reign, Hammurabi made an alliance with the powerful Assyrians to the north. It was during the reign of Hammurabi in eighteenth century BCE that Babylon rose as a center of power and the administrative capital of a new Mesopotamian empire ( Figure 4.4). Indeed, at this time, it was just one of a handful of small states making up a loose coalition in Mesopotamia. But this expansion was modest, and by about 1800 BCE, Babylon controlled only a relatively small territory around the city itself. His successors expanded their control over the surrounding area, building public works projects and digging canals. Akkadian speakers of the area called it Bab-ili, which meant “gateway of the gods.” In 1894 BCE, an Amorite chieftain named Sumu-adum took the city and installed himself as ruler. Its name is of unknown origin and was likely pronounced Babil. Unlike Ur, Babylon had not previously been an important city-state. The Rise of Babylonĭuring the later stages of the competition between Isin and Larsa, a new power emerged in southern Mesopotamia. The drive for dominance stoked the same kinds of innovation and expansion that had characterized the first city, Ur. They also embraced the political culture of rivalry, and their two most prominent cities, Isin and Larsa, fought for supremacy. They adopted the region’s existing religious traditions, its local customs, and the Akkadian language. In that year, it too was sacked by the Elamites and others.Īmorites then spread out across Mesopotamia, establishing powerful cities of their own. By around 2004 BCE, all that remained of Ibbi-Sin’s empire was the city of Ur itself. As raids by these groups increased in volume and intensity, city after city fell, and the Third Dynasty of Ur disintegrated. They were soon joined by the Elamites from the east. The strategy ultimately failed, and in the reign of Shu-Sin’s son Ibbi-Sin, the Amorites breached the wall and began attacking cities. Raiding by these Amorites was considered such a problem that in approximately 2034 BCE, Shu-Sin, ruler of Ur, constructed a 170-mile wall from the banks of the Euphrates to the Tigris to keep them out. One of the greatest threats came from nomadic peoples then living in the desert regions of Syria. Foreign invaders from the north, east, and west put tremendous pressure on the rulers of the Third Dynasty of Ur, the last Sumerian dynasty. The end of the third millennium BCE was a transformative, if sometimes chaotic, period in Mesopotamia. From the archaeological record and surviving documents, historians have cataloged these groups and learned a little about how they lived. Within these different empires existed a diverse assortment of peoples, social classes, religions, and daily practices. Later powers like the Hittites, Neo-Assyrians, and Neo-Babylonians continued to borrow from earlier empires and added unique traits as well. The Third Dynasty of Ur and Hammurabi’s Babylonian kingdom were in many ways imitators of Sargon’s earlier example. Though it lasted only about a century and a half, his model of imperial expansion and administration was followed by a number of successive regional powers in the region. When Sargon of Akkad built Mesopotamia’s first empire in approximately 2300 BCE, he inaugurated a new era in the Near East. Explain how city-states of the Ancient Near East interacted with their neighbors.Discuss the political norms, technological innovations, and unique social attributes of the major city-states of the Ancient Near East.Describe the geography of the Ancient Near East.By the end of this section, you will be able to:

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)